And yes, indeed, there is much rejoicing.

However…there is also a stinkin’ huge amount of get-your-hands-dirty, fry-your-brain work. I haven’t had a lot of downtime lately.

Which is why this week’s WILAWriTWe is going to be short and sweet. (Let all the inklings say yeah.) 😉

The One Where I’m A Perfectionist

Oh, had I not mentioned that before? Well, it’s true. I’m a perfectionist. Yes, I get it that it’s often an unrealistic mindset. Yes, I understand it’s a control issue. Yes, I understand it’s a boundary problem within my own head.

Hallelujah, I’ve been aware of these things for a long time, and I’ve been working on decreasing the intensity of my perfectionism for a long time, and I’ve actually gotten better, sha-zam.

But there are some things about which I cannot be perfectionist. Not because I don’t want to be. But because I simply can’t. The situation is so far beyond my control, there is no possibility at all of my getting my perfectionist way about it.

One of these things is my hair. I love the pixie cut I’ve adopted over the past 8 months; it’s the first style I’ve enjoyed with complete, unadulterated passion.

But the fact remains that as much as I love the cut, the nature of my hair will forever be outside my control. My hair is baby-fine. I’d like to have about 50% more of it.

I will never, ever have the thick, luxurious mane of auburn hair that I would so very dearly love to have. I got baby-fine-hair gene from both of my parents. Genetically, I was doomed before birth never to be a hair model.

This is beyond my control. My hair will never live up to my standards. I cannot be perfectionist about it.

I can’t be perfectionist about the format of my book for Kindle, either.

This Is the Part Where It Gets Short & Sweet

I promise.

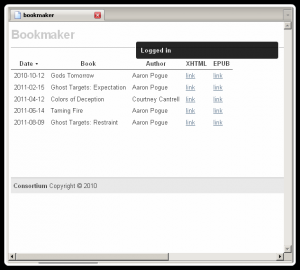

Last night, I started proofing the Kindle version of Colors of Deception. Aaron warned me that I would find formatting errors that, because of the nature of Kindle, we will be unable to correct. When he informed me of this, I nodded sagely and assured him I could handle the reality of the situation.

I can handle it.

I can handle it.

I swear I can.

See? This is me. Handling it. I’m fine. Really.

*sigh*

Yeah, those formatting errors are there. And because of the coding or whatever behind the Kindle text, there’s nothing we can do about it.

In the hopes that maybe you won’t notice them, dear inklings, I’m not going to delineate for you what those errors are. Not because I doubt your error-spotting prowess, but because I’m hoping you’ll be less perfectionist about all this than I am. After all, this is my kid, not yours. You’re not gonna check behind its ears. All you wanna do is read it (I hope).

In Which I Get All Conclusion-Drawing-y and Stuff

The thing is, this was always going to happen. I was always going to publish a less-than-perfect book, dear readers — because there is no such thing as a perfect book.

This afternoon, I start proofing the .pdf that will eventually become the printed paperback. When those paperbacks are printed, they will contain errors. So far, seven other people besides me have proofed this book. I myself have read it uncountable times. And guess what? Last week, I found a typo that none of us had previously caught.

Was that the last typo? The only error left in the entire manuscript?

You bet yer patootie it wasn’t.

There will always be something left to fix. That’s the nature of books. Even if we did manage to eliminate all the spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors, I could still find something to fix with every new read-through.

I could easily spend the rest of my life tinkering around on this single manuscript. I would do it, if I let my perfectionism get the best of me.

But if I did, I would never publish the book. Or any book. In which case the entire exercise becomes moot. Why tinker around on a book that nobody will ever read?

So I’m letting go. I’m putting out my book for the world to see, and I’m doing it in full knowledge that the book contains mistakes. Sure, I’m going to do my absolute best to eliminate as many errors as possible before Launch Day — but launch I shall, and in understanding that the book isn’t perfect.

And guess what?

It’s perfectly okay.

And that’s WILAWriTWe.