We’ve been talking about long synopses and scene lists this week. Yesterday I went into some detail on what scene lists are for.

Today I want to tell you how to write one. It shouldn’t be hard, but it’s definitely going to take some time and thought. So let’s get started!

Meat on the Bones

By this point in your prewriting process, you have everything you need to make a story. You’ve got a beginning and an end. You’ve got characters, you’ve got conflict, you’ve got an overview of the plot. Making the novel requires you to flesh out that skeleton, though.

If you want, you can jump straight into writing and achieve that. I find I always benefit from one last bit of structure, though. With a beginning, an end, and a few big plot points, you’ve got a general direction, but a scene list gives you every turn along the way.

That’s really what I was talking about yesterday. Your story arc (your short plot synopsis) determines what needs to happen, big picture, as you move from beginning to end. Building a scene list helps you extrapolate from that to figure out what needs to happen in any given chapter, any given scene.

What Needs to Get Done

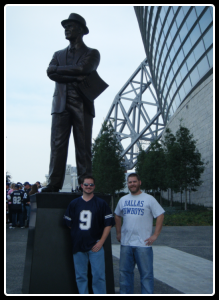

It’s like the list I shared about my weekend. I knew all the big things that had to happen — Consortium party Sunday, Cowboys game on Monday, homework due on Tuesday — and then I broke it down into smaller parts to figure out how I would get from one to the next, and in each of the smaller parts I had something that needed to happen. If I missed that, the next step in the path wouldn’t really work out right.

A lot of the time when you come up with a story idea, it’s just a beginning or an end. You have an idea for a really cool scene, and you want to make that happen. You do some thinking (or work through some prewriting exercises), and you figure out how to turn one idea into a whole story.

That’s enough to get most people to commit to NaNoWriMo. It’s big, it’s exciting, and it feels almost doable. If you have that much, you’ll probably make it at least a week into November. That’s my experience.

What usually stops people after that first week is sandbars, roadblocks — writer’s block. You know the story you want to tell, you know where it’s supposed to go, but right now (in the middle of chapter three or 200 words into a Tuesday that needs to see 1,667 words written), you just have no idea how to get there.

The answer, as I promised yesterday, is a scene list. The answer is scenes. Scenes are the stepping stones that get from one big cool event to the next one. And, like I said yesterday, a scene list tells you at ever step of the way what happens next.

Your NaNoWriMo Scene List

So let’s get started. If your experience is anything like mine, your scene list should probably be 5-10 pages (give or take 2), but it depends on the complexity and the length of your story.

So let’s get started. If your experience is anything like mine, your scene list should probably be 5-10 pages (give or take 2), but it depends on the complexity and the length of your story.

Create a list of every major scene in your novel, explaining for each scene (in 2-5 sentences) what characters are involved, what they do, and what impact it has on the story.

I recommend starting with your Table of Contents and expanding from there. In fact, if you wrote out the old-timey chapter titles as I described in that article, you’re probably half done. Expand those sentences into paragraphs. Explain anything that isn’t clear.

Give away the ending, too. This is for you, and if you don’t know your ending, you can’t really write the beginning and middle. If you haven’t thought it through yet, now’s the time.

When you’re done, you should have a complete story down on paper. Then all that’s left is writing. And that’s exactly what November is for.