Once upon a time, you had to write an intro.

Maybe it was for a business letter (probably a query letter, if you’re one of my Creative Writing readers). Maybe it was for a memo you had to write at work. More likely it was for an English class, or the essay portion of an exam. You had the whole body of your document ready, carefully crafted, ready to spill upon the page, but you found yourself hesitating at the first line. You had no idea how to start.

That’s a normal problem. Actually, no, it’s a whole handful of normal problems. Sometimes you have no idea what to say in the introduction. Sometimes you know exactly what you want to say, but you have no idea how to get started. Sometimes you know exactly what you want to say, but what you want to say is the body of your document so there’s no point to an introduction. Sometimes you know exactly what you want to say, but it’s way, way too complicated to sum up, and you don’t even know where to start.

And, of course, sometimes you have no idea what to say at all. You don’t have the body of your document ready, but you need to get started somewhere. All of these problems come crashing together at the bottleneck that is the intro. The first paragraph. The first word. Once upon a time, you had to write an intro, and chances are pretty good you hated it.

The Other Problem

In all that list of problems you might have encountered, there was a big one missing: the reader’s.

I hinted at this issue back in my introduction to the series, but it’s critical to understanding the problem of introductions, and it’s the key to taking the stress out of writing your own. The problem is the gap between what you know (as the writer) and what your reader knows (as the reader). See, there’s something else that happened once upon a time. Once upon a time, you picked up a business letter, or a memo, or an essay someone else had written, and you found yourself two or three paragraphs in, wondering what it was you were reading.

Good readers are able to figure out what a document is about, and what they can get out of it. Good writers don’t make them.

The purpose of an introduction is to bring the reader up to speed. A friend of mine called it a roadmap. It’s an overview of what this document is, and where it’s going. A good introduction completely brings the reader into the conversation, and then the body of the document carries on the discussion.

An Introduction to Metadata

Another way of saying that, without all the metaphors, is that an introduction establishes the document’s context. That’s complicated a little bit by the fact that every document has another element that also works to establish context, and it’s likely one you’ve never thought much about — the document type itself.

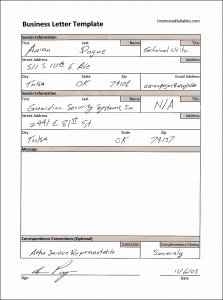

I often refer to this as the document’s metadata, the information conveyed by the document, but not conveyed within the introduction, body, or conclusion. In a business letter, this includes the letterhead, the date, and the addressee. In a memo, it’s the subject line. In a paperback novel, it’s the cover art and the glowing recommendation by Stephen King. Every part of the document, every element of the template and format conveys information to the reader, and all of this information establishes an expectation before the reader ever gets to the first word of the actual message.

I may talk about document metadata at more length in the final post in this series, but it’s important to introduce it now, because it impacts your introduction. Your introduction needs to establish the context of your document, and then get out of the way. If your document’s metadata includes your name, you probably don’t need to include your name in the introduction. If your document’s metadata includes a detailed subject line, you probably don’t need to include that subject verbatim in the introduction. Your introduction is an opportunity to present all of the contextual information a reader would need to get into the body of your document, that isn’t already present in the document’s metadata.

Of course, sometimes your metadata betrays you. Sometimes you need to use your introduction to correct a reader’s wrong assumptions. Maybe you’re writing a friendly, creative message in a formal, professional business letter format. Use your introduction as an opportunity to change the reader’s expectations by establishing a different voice. Maybe you’re releasing a serious, time-sensitive policy memo as a company-wide email. Use your introduction to clarify the special circumstances and make sure your readers know what is expected of them.

Writing a Good Introduction

When I started my first day teaching Technical Writing last fall, I got up in front of the class…and froze. My heart raced, and my words failed me. I looked out at all those eyes, all those students waiting to hear my words of wisdom, and all I could think about was my paralyzing panic.

My dad is (among many other things) a Speech professor, and when I told him about that experience, he had some simple advice for me. “Think about the students.” He said that any public speaker, no matter how practiced, how polished, how perfect, would lock up just like I did if they let themselves get caught in a cycle of self-evaluation while presenting to a crowd. It’s human nature. He said the key was to turn my attention outward, to think about what it was the students needed to know, and focus on answering that need, and then the words would come easily.

He was right. I probably wouldn’t have survived the semester without that one bit of advice, but it was spot on. And, when it comes right down to it, that’s also the key to writing great introductions. Don’t think about your paper. Don’t think about your document’s body, or your list of points, or how smooth or silly your opening line is. Think about your reader. Think about the person or people who will be reading this document (now, and in the future), and tell them what they need to know.

I’ve given you some samples of things they might be looking for in the discussion of metadata, but that’s only a portion of it. You’ll need to establish your general topic. Maybe you need to clarify whether this document is informative or persuasive. Maybe you need to clarify whether this document is entertaining or technical. Maybe you need to provide an executive summary — a quick overview of the document’s contents — and maybe you don’t.

If that’s aggravatingly vague, it’s because every document is different. There are some standard elements from document type to document type, and I’ll try to hit on those in more detail when I discuss the document types directly, but for the document you’re working on right now, it’s enough to know that the purpose of the introduction is to bring the reader up to speed. When you launch into that opening sentence, you’re not discussing your topic yet. You’re not perfecting presentation, or conveying information. Right now, you’re not even communicating.

Instead, focus on that disconnect and do what’s necessary to fix it. Figure out where your reader is, and where your document takes place, and say the words that need to be said to create a link between the two. That’s what I mean when I talk about negotiating a connection. That’s a good introduction.

Photo credit aussiegall.