My fantasy world, in all its glory.

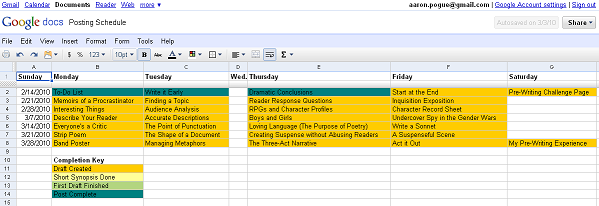

I’ve talked a lot about the Technical Writing class I taught last fall, but I’ve rarely said a word about the time I took that class, eight years back. One of the coolest parts of that class (both times) was the big bad Semester Project. Every student has to pick a topic early in the semester, prepare a proposal and a couple progress reports, defend the proposal before the professor, develop a major documentation product, and finally give a report to the class at the end of the semester.

When I went through that course, I was waist-deep in my second big rewrite of my second novel, and gearing up for my first serious bid for publication. So for my documentation product, I put together a formal market analysis and submission package for my novel. I spent the whole semester researching agents and editors, practicing query letters and refining my plot synopsis. It was one of the most useful projects I did in my entire college career. I enjoyed every moment of it, right up until the end.

At the end, as I said, I had to do a presentation. Public speaking has never been my strong suit, but I kept telling myself, “On this topic, I’m an expert. I’m the expert. There’s nothing to worry about.”

Then the time came for my presentation, and I stepped up to the front of the class — a class filled almost entirely with Engineering and Business Majors.

I put up my first slide — a badass drawing of a growling dragon that I hoped to use as cover art — and all it got was a blank stare. I said, “For my project, I prepared a promotional packet for my fantasy novel, Taming Fire. It’s the story of an orphan boy who just wants to join the army, but ends up riding dragons and battling with some of the world’s most powerful wizards….”

This was before Harry Potter and the Lord of the Rings movies brought fantasy mainstream. It was before Napoleon Dynamite shone a bright light on the miserable life of the truly excellent nerd. I met the eyes of everyone in the audience, as I’d been trained to do, and I saw bafflement and confusion. Somebody snickered. In that moment, I felt like such a little dork, talking to these engineers and businesspeople about my private fairytale. I had two more minutes of synopsis to give, though, before I was supposed to transition to the actual project — my research, the documents I’d written, and what I’d learned. Two minutes of dragons and dwarves and elves and magic.

Those were probably the longest, most painful two minutes of my life so far. It was brutal.

Story Summaries

There’s an easy lesson to be made here about audience analysis, but I want to talk more specifically about story descriptions. The saddest part of that story is that I’d spent the whole semester studying synopses, refining my story description, reworking it in new formats, but even after all that work, it was my story description that brought me down.

I could have come up with a description of the project that wouldn’t have left me feeling so stupid in that crowd. I didn’t, because I’d spent so long thinking about and writing to agents deeply entrenched in the fantasy genre. That’s where the audience analysis comes in. It also points to another need most new writers overlook: your book needs a good description. In fact, it needs several.

Why? Because people are going to ask. Even if it’s not for a class presentation, at some point someone’s going to ask you to describe what your book is about. That can — and should — be a magical moment. That’s an audience interested in this things you’ve been working so hard on. If you’re not prepared, though, it can be almost as awkward as my presentation was.

So start with that. Arm yourself up against the circumstance. Figure out exactly how you would describe your book to someone who’s not in your target market. Write it down. Aim for two or three pages, but if it’s shorter than that (or longer), that’s fine. Whatever it is, though, make sure it accurately describes your project, and that it does so in a way you would be comfortable sharing with a stranger.

When you’ve done that, you’ve done the hard work. You’ve captured, in a handful of pages, what your story is. You’re not relying on genre lingo or artificially easy comparisons to do the heavy lifting. You do still have some work to do, because (when it comes right down to it) that synopsis is the least useful one you’ll ever write.

It’s a fantastic starting point, though.

The Many Types of Plot Synopsis

The other types of book description all exist for very specific purposes. They include (and these are just my names for them):

- The complete synopsis (or scene list)

- The long synopsis (which is usually two to five pages)

- The short synopsis (one full page)

- The pitch (two to four paragraphs)

- The tagline

- The formula compare (something like, “It’s Rivendell meets Friends.”)

That’s a lot of different descriptions, and even though they vary in length, it’s usually not too easy to convert one into another. That’s because, as I said, they serve different purposes. For all of them, I would start with your audience-neutral description you did first, and work from there.

The Scene List

A scene list is primarily useful as a prewriting or editing tool. It forces you to map out the actual structure of your story, down to the very building blocks, and then gives you an easy place to spot errors or weak points, to tinker and rearrange.

To make a scene list, you start at the very beginning of your story, and write one to two paragraphs describing what happens in every scene. When you’re finished, you’ll have your entire plot down on paper — every twist and every turn — without all that messy set design, characterization, and description.

I have known of some editors or agents who wanted, essentially, a scene list when they requested a synopsis. That’s because some editors and agents want to know how well you can build a story, not just how pretty your words are. Nothing reveals your ability with story structure more clearly than a complete scene list.

The Long Synopsis

Actually, that’s the purpose of all three synopsis types — to show how good you are at building a book (or, anyway, how well this one is built). The problem is, a scene list can be a tedious affair, and every agent or editor I’ve ever known is just ridiculously busy.

As a result, most of them want something shorter than a scene list (which could easily run to fifteen or twenty pages). Instead of accounting for every brick in the wall, they just want a scale model. You job is to convey the shape of your novel, including the beginning, the major obstacles along the way, and the end.

Yes. The end. Writing a solid climax and satisfying resolution is one of the hardest parts of storytelling, so you have to tell the end. Worried about it seeming flat and boring? Good. Work hard at making it sound just as powerful and interesting as it really is, even if you’ve only got a page to do so.

The Short Synopsis

You should really be doing that for the whole book anyway, and when you get to the short synopsis, you’ve only got one page for all of it.

When it comes to the short synopsis, you can think of it more like the stuff you’d find on the back cover of a paperback. It’s almost marketing material, drumming up a powerful intro and characterization, hinting at a world, and suggesting a direction for the plot. Give yourself two-thirds of a page to do all that, then start a new paragraph and give away the ending. Briefly sum up the plot (the middle), and the climax and denouement (the end).

This is probably what most agents are looking for when they ask you to attach a “synopsis” to your query letter. Ninety-five percent of the time, they’re either looking for this, or the long synopsis I described above (which is why it’s good to go ahead and prepare them both).

Figuring out which one a particular agent prefers can take some serious research, and sometimes it’s just plain impossible. In those cases, I’d just go with the one you think better sells your storytelling.

The Pitch

Once you’ve got the short synopsis done, you’re nearly finished. The rest are much shorter, starting with the pitch.

The pitch is most of the body of a query letter. It is, in essence, your book’s elevator pitch. It’s two to four paragraphs that express, to an audience already prepared to appreciate it, exactly what is awesome about your book. It’s very much a sales pitch, and if you undersell your book in the query letter, chances are the agent won’t ever bother reading the attached synopsis.

On the bright side, though, once you’ve got your pitch perfect, you have already finished writing most of your query letter — a task many authors dread.

The Tagline and the Formula Compare

That just leaves your one-liners. A tagline is the one-sentence description you might see on a movie poster. Something like,

“In a world overrun by flying fish, only a maniac paperboy stands a chance.”

Or (and this one is near and dear to my heart),

“It’s like 1984, but happy.”

I like to use the tagline as the second sentence in my query letter (following close on the heels of, “I’d like you to represent my novel”). Then I personalize, give some qualifications, and follow up with the pitch. That’s your whole query letter, in a nutshell.

The formula compare is similar to the tagline, but more cynical. The formula compare suggests any new story can be described as a (sometimes clever) combination of two known stories. “It’s Cinderella meets Die Hard,” or “It’s Twilight, but with vampires.” Something along those lines.

The formula compare is lousy marketing copy, but it’s incredibly helpful shorthand. At the very least, you should come up with a comparison you like, so you can offer it as an alternative when someone describes your work with one you don’t.

Photo credit Aaron Pogue.