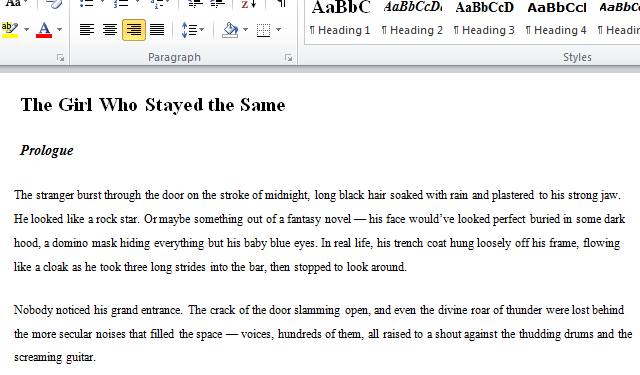

Greetings, dearest inklings. It’s lovely to see you again. Or be read by you again, if you’ll pardon the passive. Or something like that. At any rate, it’s good to be back WILAWriTWe-ing again.

Greetings, dearest inklings. It’s lovely to see you again. Or be read by you again, if you’ll pardon the passive. Or something like that. At any rate, it’s good to be back WILAWriTWe-ing again.

“Oh?” some of you might be asking. “Back? Again?” In other words, though I know for certain that some of you missed me, I’m sure there are those among you who didn’t notice my glaring lack of article for Unstressed Syllables last week.

So, to those who didn’t notice that you missed anything: You didn’t miss anything, because there was nothing to miss. And to those who spent last Wednesday morning weeping into your coffee whilst desperately scouring the blog, hoping against hope that I merely made an error in timestamping and you might locate the day’s WILAWriTWe somewhere in the vast nether regions of Unstresssed Syllables’ archives…to you, I can only say I’m sorry — and I dedicate the following story to you.

The Unexpected Guest

Just under two weeks ago, four days before I was supposed to post the WILAWriTWe that ended up getting neither written nor posted, I found a kitten abandoned in our parking lot. I cannot but believe this small creature was meant to enter my life and the lives of my skeptical husband and adult cat, for I heard the little thing’s cries from inside my apartment, over the blaring of the movie The Blind Side , and in spite of the hissing of the air conditioner. And once outside, pattering around the apartment complex barefoot, I simply couldn’t resist rescuing the little ball of fluff that came bounding out from underneath a car as I approached, bleating its little kitten heart out in gratitude at finding a human savior.

, and in spite of the hissing of the air conditioner. And once outside, pattering around the apartment complex barefoot, I simply couldn’t resist rescuing the little ball of fluff that came bounding out from underneath a car as I approached, bleating its little kitten heart out in gratitude at finding a human savior.

Much to Ed’s chagrin and Pippin’s dismay, I brought the kitten inside and installed her in our bathroom. Flea-bitten and malnourished and almost certainly wormy, she attacked the goat’s milk I gave her as though she’d never seen food before. When I softened up some of Pippin’s dry food and carried it into the bathroom, sharp and demanding meows met me at the door. Even with food in her belly, she wouldn’t stop crying, so I wrapped her in a blanket and held her while the put-upon husband and I finished the movie. Pippin watched with pupils the size and temperature of cranked-up burners on a stovetop.

The next few days were a whirlwind of kitten food purchases, flea treatments, and frustrating discussions regarding the future fate of our furry foundling. (And yes, I had oodles of fun writing the preceding sentence.) Technically, keeping her was not an option, because our apartment complex doesn’t allow more than one pet per apartment. Not to mention the fact that the husband and the dominant feline were not thrilled about a new addition, period. Things finally came to a head when I said that our bathroom was too small — and a shelter would just put her in a cage.

Ed’s response to that: “Well…I guess she needs a name, then.”

Merry and Pippin

We already had a female cat bearing a male hobbit’s name — so “Merry” seemed the obvious choice. Though nothing was official yet, the back of my mind was already carrying on conversations with non-LotR fans, in which I patiently explained that our younger cat was not, in fact, named after the mother of Jesus. But before we sat down to discuss names and decide on one, I noticed that the as-yet-unnamed fluffball was a bit less perky than she’d been the day before. This was Tuesday afternoon. By Tuesday night, Quintessential Rambunctious Kitten had morphed into Lethargic Listless Kitten — who refused to eat or drink.

Wednesday morning found me at the vet with QRK-turned-LLK, listing her woes to a white-coated young man who listened and nodded and then took her off to poke and prod and give provender in the form of subcutaneous fluids. With orders to watch her and to pay attention to her stool, I took her home again and fretted the rest of the day.

Things started looking up when, about ten hours later, the stool-watching turned into complete gross-out. I promise, the only detail you need to know is that my prediction of worminess proved accurate. Before I went to bed, soon-to-be-Merry lived up to her unofficial name by eatin’ some vittles and batting her toy mouse around the bathroom floor.

As of today, we have an adult cat named Pippin, who inhabits all rooms of the apartment with the exception of the bathroom, and a kitten named Merry, who lives in the bathroom and comes out twice a day for supervised visits with the big kitty. Cat-and-kitten integration is a slow process, so our living situation will likely continue in a state of slight chaos for a while.

But, as I’ve been assured time and again by my friends who have children, slight to moderate to total chaos is what happens when you bring a baby into the family. Floors get messy, shower curtains get shredded, and older siblings harbor jealousy and resentment. Thankfully, kittens grow up a lot faster than human babies, and adult cats have shorter memories than five-year-olds.

Excuse Me?

All of that, of course, on top of all the other ins-and-outs and ups-and-downs of daily life, is the reason I forgot what day it was and failed to post, yea verily failed to write, last week’s WILAWriTWe. “That’s a nice excuse,” thinks you, “but an excuse is all it is. What’s that got to do with writing, eh?”

Dear, still-faithful-I-hope readers, of course I wouldn’t offer you a tall tale without drawing some writerly conclusion from it. So go grab yourself another cup of coffee, make sure the boss isn’t catching you reading for fun, and let’s wrap this thing up with some tidy real-writing-life application.

Protect, Nurture, and Socialize

Your story, dear reader, is a kitten. And your job is to grow it into an adult cat. I expect some of you probably don’t care for cats much, so this metaphor might turn you off — but bear with me. It’ll all work out, I promise.

In its early stages — say, the first couple drafts — your story is rambunctious. You try to impose limits on it, but it’s mostly out of your control, skittering hither and yon and having the most glorious time making a complete nuisance of itself.

It demands your attention — especially when you try to focus on other things — and if you don’t keep a watchful eye on it, it gets itself into predicaments it can’t get out of. Its appetite is insatiable; your job is to feed it as much as it wants.

You know you need to let it out, let it stretch its legs, let it play — but at the same time, you have to protect it from The Dangers Of Outside. You are its guardian and its advocate, and you must commit yourself to diligence and vigilance. (Ha! Say those two words ten times fast!)

Sometimes, your new story gets a little sick. Sometimes, your new story gets a lot sick. You’ve dealt with stories before; you generally know what to do to get them back on track. But sometimes, what you know doesn’t help — and then it’s time to wrap that story up so it stays warm and cozy, then take it to someone who can look at it for you.

Sometimes, that someone has to take your story away, so as to give it the painful yet ultimately beneficial treatment it needs…without your nervous and unnerving interference. So just sit back, try not to fret, and trust that your beta reader knows what she’s doing.

She’ll bring your story back, give a few bits of advice, and send you home to spend more time with the little thing. Sometimes, you’ll have to bring it back for a second round of treatment. But I’d venture to say that most often, you’ll take it home and discover that after some unpleasant purging of unnecessary bits, your story is much improved and more than ready to come out and play again.

And what of the sibling rivalry? Your well-crafted stories look down from their lofty heights of final draft completion and say, “What is this nonsense? Who brought this youngster in? We cannot be expected to mingle with this.”

Oh, but yes — those elder siblings have experience, and it is their job to teach your little story what it needs to know. Your completed works know so many things the little one must learn: story structure (this home has order), interaction with readers (it’s not good to claw them), and the slow but exhilarating process of growing up (one little pawstep at a time). Your completed stories are the embodiment of lessons well learned — and lessons applied.

It’s your job to communicate that acquired wisdom to the new story, turning theory into practice. It’s the best way to prepare your story for socializing with the readers who come to call.

And that’s WILAWriTWe!

(Click the Amazon link, buy something within the same browser session, and I get a few pennies with which to purchase the increased amounts of catfood required by my household. Thanks!)

Photo credit Julie V. Photography.