A radar tower can be a dangerous place, unless you've got the right documentation (photo courtesy dieselgression at Flickr | CC BY 2.0)

My first job out of college, I was a Technical Writer for a small manufacturer in Tulsa, Oklahoma, that produced some of the world’s best fish finders. I spent several years writing user manuals for gadgets. Then I took a new job working for the Federal Aviation Administration, where I wrote maintenance instructions for the field technicians who service and maintain our nation’s long-range radars.

They dropped me in a cubicle with mountains of documentation — literally thousands of pages describing the systems I was going to be writing about — and suggested that I try to get up to speed. I was about two weeks into that process, and just starting to feel like I had a grasp on things, when an Engineer stopped by my desk one morning, coffee mug in hand.

“Whatcha working on?” he said, jabbing his chin at the old yellowed book I was reading. “That an ARSR-4 book?”

I nodded. “I finally figured out how to read the family tree,” I said. “So now I’m having to reread all the part descriptions.”

He snickered at that, then asked seriously, “You seen one yet?” When I shook my head, his eyes got wide, and he said, “Oh, we’re gonna have to fix that!”

I had no say in it. He got me on my feet and down the hall, then I climbed into his beat up old truck and we bounced down the lane, away from the pretty, air-conditioned offices to the big, angry orange radar tower spinning on the far corner of our lot. He led me into a rickety tinker-toy elevator cage and hit a lever to send us a hundred feet up into the belly of the beast.

At the top, he opened the cage door, and I followed him out into a cramped little room, packed with electronics and machinery, and rumbling with the constant growl of the sail spinning just above our heads. He smacked a hand up against a big sheet metal box, and said, “Recognize this?”

“Air handling unit?” I guessed, trying to correlate the block diagrams in the forty-year-old manual to the things I was seeing in real life. He nodded in satisfaction.

“That’s right. And this?” He pointed to a cabinet full of relays and switches, green lights glowing in a row on its front door, and I just shook my head. I knew already that the air handling unit was going to be the only one I got right.

So he started telling me. We walked all the way around the room, him pointing to cabinets and cable conduits and even the computer — the only computer in the room — and shaking his head in disappointment when I didn’t know what any of them were.

“What were you reading just now? When I stopped by.”

“Repair and replace procedures for power supplies,” I said, and he nodded.

He led me to the cabinet for the particular piece of machinery we’d been talking about, flipped the door open, and said, “There you go. Where’s the power supplies?”

I recognized them right away, big gray blocks I’d seen in low-rez photos in the manual, so I pointed and he nodded. “And do you remember how the procedure went?”

“First, I shut off the power supply to the APU,” I said, reaching out just to point to it, but his hand shot out like lightning to intercept mine, and locked on my wrist with a vice grip.

“Not that one,” he said. “If you throw that switch and go on with the procedure, you’re going to end up a blackened lump up here in the tower, and we’ll have to buy us a whole lot of new parts to get this thing running again.” He moved my hand down and to the left, until I was pointing to a power supply on a totally different block, and said, “That’s the one for this procedure.”

I nodded, and backed away, and didn’t touch a thing for the rest of the visit. By the time I got back to my cubicle, I was ready to take those part descriptions a lot more seriously.

Clarity Saves Lives

As a Technical Writer, I make my living off accurate descriptions. Sometimes it’s enough to say, “Shut off the power supply,” but in a system like the one I was shown, “Shut off the +/- 5 VAC Power Supply on the APU path,” might not be enough detail — especially for a rookie Tech Writer fresh off the bus.

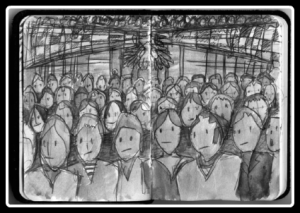

I’m sharing this story because I know you can sympathize. Maybe you haven’t been standing with your hand hovering two inches from a switch that could kill you, but you’ve run into bad descriptions in your time. Writing is all about description — it’s about creating symbolic references to real things, whether you’re talking about physical objects or life experiences. No matter how good the style, how perfect the template, a document with weak or confusing descriptions isn’t doing its job.

Getting it right is a tricky process, though. It draws on skills I’ve been talking about for months, the most important being audience analysis. You’ve got to negotiate a connection and then translate understanding. In other words, as in all good writing, you have to consider the reader’s experience if you’re going to get it right.

That was the problem I ran into, up in the radar tower. It wasn’t just that I was new to the job, or that I’d had trouble following all the descriptions in the book. Part of the problem was that the book was never written to me.

If I took you up to that cabinet and told you to shut off the +/- 5 VAC power supply on the APU path, it wouldn’t mean a thing. Unless you’re a trained technician, all that detail is worthless to you. I’d be better off saying, “Open the big red cabinet and look for three rows of grayish boxes on the left wall. Flip the switch on the first box in the bottom row.”

When I get these instructions from my Engineers to include in the procedures, they usually look more like, “Turn off A1C3A2A1A1.”

All of those descriptions refer to the same device, the same action, and any of them can be called an accurate description. The best way to describe something depends highly on context.

Getting it Right

That’s not to say there’s no right way to do it. In my case, the right description is the one that allows my reader to cut power to the APU path so he can perform the rest of the procedure without getting electrocuted. In every case, the right description is the one that works.

If you’re a blogger, the one that works is the one that clearly speaks to your niche readers. If you’re reviewing a product, you need a description of it that gives a clear impression. If you’re telling a sad story, you need a description of events that evokes emotion. If you’re begging for technical assistance from your readers, you need a description of the problem that includes your personal setup and the desired outcome.

The trick, then, is to think ahead. It’s not enough to stumble into your description, tossing in whatever information strikes you. Consider what you’re trying to accomplish, and consider who will be reading it, then write directly to that target. Get it right, and nobody gets hurt.