The student of writing can come up with myriad metaphors for what writing is like. Call it painting. Call it shipbuilding. Call it a political race. Let me tell you one of my favorites.

Writing is like sculpting. You take this raw idea and you cut away the unnecessary, the amorphous. What is left is a polished and unique representation of some aspect of the world.

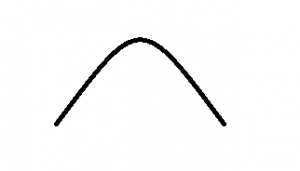

The surprising thing about writing is that every good story is shaped roughly the same.

All of them. It’s ingrained in the human mind—I think it’s instinct—that if a story isn’t shaped like that, it isn’t good.

This arc is a diagram of what the action looks like in a story. It starts small as you introduce your readers to your world and your characters and your problems. Then it grows. There’s tension. There’s suspense. It all culminates with the height of the action, the climax of the story, where all of the characters and problems come together and require resolution. Once the climax is over, the action falls. The crises are resolved for good or ill. The characters have changed. There is a new baseline in your world.

Now, the arc above is extremely simplified. For one thing, you won’t spend nearly as much time winding down a story as you will winding it up. That was the convention a long time ago; Shakespeare’s plays are extremely symmetrical. These days we tend to have the climax at the very end and only spend, at most, a chapter or two describing how things calm down and what kind of normalcy prevails after the climax.

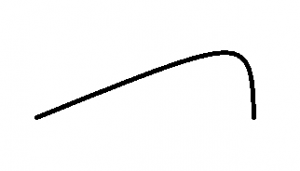

So really your book is shaped more like this.

And even that is oversimplified. The action in a good book doesn’t rise smoothly. Your book is made up of scenes, and some of these scenes are going to be more active than others. So the line of your plot arc is really going to be very jagged.

And then there are the really pivotal scenes. I call them plot points. You can think of them as mini-climaxes. These are the ones where the tension spikes for a moment as a new plot twist or conflict is introduced. The action then dies down a little before rising again toward the true climax.

So an accurate representation of the shape of your book would really be like this.

Sound complex? It is at first, but if you spend enough time writing stories it becomes like second nature. And let me reiterate that this is universal. All good stories follow this pattern.

Take, for instance, the first Star Wars movie (Episode IV: A New Hope). Our baseline is that there is a galactic rebellion against the evil empire, and there is a kid named Luke who, unbeknownst to him (but knownst to us), is being drawn toward that rebellion. The tension rises until the first plot point, where Luke is ambushed in the desert. This plot point introduces a key character (Obi-Wan Kenobi), and then the action dies down a little as they go into town.

The tension then continues to rise as they get a pilot and leave town, discover the Death Star, infiltrate it, and rescue the princess. This leads to the next plot point where Obi-Wan is killed by Darth Vader. Then the characters fly away and the action dies down, only to continue to rise as the Death Star now poses a threat to the rebels. The climax finally arrives in the form of an epic battle between the Death Star and a ragtag group of freedom fighters. The conflict is resolved when the Death Star is blown to smithereens, and there is a scene of falling action as our heroes are rewarded.

Star Wars follows our pattern precisely. Interspersed throughout the plot points are smaller bits of rising and falling action that slowly work up toward the ultimate moment of conflict and resolution.

It’s not just Star Wars. Lord of the Rings does it, both within each book and as a whole. The Count of Monte Cristo does it, V for Vendetta does it, The Great Mouse Detective does it, and you can even see it in each and every episode of Law and Order. Show me even a moderately good story, and in five minutes I can draw for you a precise and detailed plot arc. Whether we are born or trained to shape stories like this, the fact is that we do.

And, wouldn’t you know it, I even shaped this article in an arc. At the beginning I introduced the idea of the plot arc. Each of my diagrams was a plot point where I gave more and more detail to the idea. I continued to heighten the tension through my demonstration of the arc’s ubiquity until this, my climax, where my master plan is finally revealed. And now we will resolve the conflict by discussing what the plot arc has to do with rewriting.

If you can perfectly shape your story so that all its facets—your plot, your character development, your thematic development, everything—fit the arc precisely on your first draft, you don’t need to be reading my blog. I need to be reading yours.

As for the rest of us, on our first draft we chisel out a very rough representation of the people and ideas that fill our story. We use our subsequent drafts to reshape them and redefine them and make sure they fit the proper structure. This is part of why a story is always better on the third draft than on the first. As we rewrite our material, we shape it to fit the arc structure that is most ideally suited for telling stories.

One of the best things you can do for your story, no matter the medium, no matter the genre, is to draw out its arc. I don’t care if you do it with paper or Play-Doh, just diagram it. When you can define what the plot points are, how the action flows between them, and how it affects what happens to your world, your characters, and your themes, you will be thinking about your work on a new, more mature, more professional level. Then, young padawan, you will know the ways of the arc.

This article required four read-throughs.

Thomas Beard is a writer and editor with the Consortium. Every Wednesday he shares an article about revision, rewriting, and story structure.

Watch for his debut epic fantasy, The Orphan Queen.